“HATE SLAVS” – HATE SPEECH IN THE BALKANS

May 28, 2021

Hate speech is commonplace in public discourse in the Balkans

Offensive language, insinuations, labelling, presenting false information about people in public discourse with no holds barred, whether it is the media or the assembly i.e., in public debates, or in messages on social media and other public platforms, has become more the norm than an exception in the Western. Balkans.

Despite the existence of both codes of ethics and legal protection, hate speech is a part of everyday life, it is shared in public without a second thought. This blog is dedicated to our “non-accountability” to what is said in public discourse. “Got killed by the harshest of words” (Ubi me prejaka reč) was a line in a song sung a long time ago by Branko Miljković, as well as many others who became victims of “hate speech” in public communication and never managed to get rid of the burden of the spoken insults, lies, labelling. Even when they would prove that they are right in court, as a rule, public opinion never stands to correct them. So, it is not a matter of penalizing “hate speech” but preventing it. This is one of the very important tasks of media literacy of young people and the citizen at large.

Code(s) of Journalists

The first level of protection against hate speech when it comes to the media, be it traditional or digital media, are the so-called professional codes of ethics. In the Code of Journalists of Serbia, hate speech is mentioned only in Chapter IV “Accountability of Journalists”:

“1. The journalist is, above all, accountable to his readers, listeners and viewers. That accountability must not be subordinated to the interests of others, and especially to the interests of publicists, the government and other state bodies. A journalist must oppose anyone who violates human rights or advocates any kind of discrimination, hate speech and incitement to violence.” Guideline 3 adds “Colloquial, derogatory and imprecise naming of a certain group is inadmissible.”

The Code of Journalists of Montenegro defines “hate speech” in much more detail on page 13 in the Guidelines for Principle 4 under 1.4 “Hate speech”, stating:

“(a) The media may not publish material intended to spread hostility or hatred towards persons because of their race, ethnicity, nationality, religion, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, physical and mental condition or illness, as well as political affiliation. The same is true if there is a high probability that publishing some material would provoke the aforementioned hostility and hatred. (b) The journalist must avoid publishing details and derogatory qualifications about race, colour, ethnicity, nationality, religion, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, physical and mental condition or illness, family status, and political affiliation, except if it is in the public interest. (c) A journalist must take special precautions not to contribute to the spread of hatred when reporting on events and phenomena that contain elements of hatred. It is the journalist’s obligation to respect other states and nations.”

In the Code of Honour of Croatian Journalists, item 13 “Fundamental Human Rights and Freedoms” states that,

“In the line of their work, journalists shall respect, protect and promote fundamental human rights and freedoms, and in particular the principle of equality of all citizens. Special accountability is expected when reporting or providing commentary on the rights, needs, problems and demands of minority societal groups. Information on race, colour, religion or nationality, age, sex, sexual orientation, gender expression, any physical or mental characteristics or disease, marital status, lifestyle, social status, financial standing or level of education shall be provided by the journalist only if it is extremely relevant to the context in which it is presented. It is inadmissible to use stereotypes, pejorative terms, debasing portrayal, as well as any other form of direct or indirect incitement or support of discrimination.”

This is the case in all other professional codes of ethics in the countries of the Western Balkans, as well as in the world, as they are based on the elementary document of this type, the so-called “Munich Declaration” from 1971. Namely, the representatives of the journalists’ trade union of six member states of the European Community adopted the “Declaration on the Rights and Obligations of Journalists of the European Community” (Lorimer, 1998, 156-158) on the basis of which many national associations of journalists and some media houses later on created their own internal codes of behaviour. Of course, the phrase “hate speech” came into public use many decades later, but the model was recognized in this document, made exactly half a century ago.

The legislation of all countries recognizes the concept of “insult” and it is a very controversial and sensitive “tort”. We will therefore quote the explanation of a very famous judge from Serbia, Miša Majić:

“When it comes to the crime of insult, things are not as simple as it may sometimes seem. What constitutes conflicting views in case law is contained in paragraph 4 of Art. 170 of the Criminal Code. Namely, it is stated here, among other things, that the perpetrator shall not be punished for an act of insult if the statement is given as part of serious criticism in a scientific, literary or artistic work, in performing official duties, the journalistic profession, political activity, defending a right or protecting legitimate interests, if it is clear from the manner of expression or from other circumstances that this was not done with the intention of belittling. Thus, the court that would have to assess, taking into consideration all the circumstances of the case, whether the statement, which is purely objectively seen as offensive (the plaintiff is a “liar”), was given in this case in defence of some rights or protection of legitimate interests, and whether the manner of expression and other circumstances indicate that this was not done with the intention of belittling. Therefore, both of these elements (circumstances + intentions) would have to be present.”

Since this “general place” can also be found in all court practices throughout the Balkans, we believe that we have resolved the basic dilemmas about whether hate speech has been “processed” in ethical and legislative practice. Yet, why is “hate speech” still very much present in public discourse and how do we curb it? The answer to these questions is not at all simple. One possible solution was given in an advocacy video of the NGO Buka from Sarajevo, which got millions of views in just a few days.

Creative indication of “excessiveness”

Here is just a part of the dialogue of this video, as an example of general non-accountability in the vocabulary choices we witness every day:

“Give me a veal shank, you fat pig.

– Will this one-pounder do, or would you like two pounds, you Turkish whore?

– One pound is fine, you Chetnik fagot.”

Marija Janković, a BBC journalist, wrote the article “Hate Slavs and the Balkans: How the Yugoslav Anthem Inspired the Fight Against Hate Speech”, on April 12, 2021. The article quotes Aleksandar Trifunović, director of Buka: “The initial inspiration for the video was the song Hey, Slavs, which was the anthem of former Yugoslavia for almost half a century”, adding: “This time we decided to fight hate speech just like the vaccines fight coronavirus – you have to put a piece of the virus in the vaccine to kill the virus. So, we had to insert a piece of hate speech to fight it.”

It seems that the video really is one of the possible solutions against hate speech, because it was broadcast on the Internet, which is a communication channel that young people prefer, so it is most likely to reach the target group online and try and make them aware and help them learn how to recognize “hate speech” and how to stand up against it. It showed, in a creative and sarcastic way, how we have completely lost our sense of etiquette, decency and communication in public speech, the goal of which should be dialogue and debate, and not insulting and belittling anyone around us who might be different.

This did not happen overnight

In essence, it all started thirty years ago, when newspaper articles in the media on the territory of the entire former Yugoslavia “fired from all available linguistic means” or as our famous sociolinguist Professor Ranko Bugarski PhD said in his book “Language from Peace to War” – it was words that were fired first on the territory of former Yugoslavia, the cannons came after. Let us also recall the war reporting of the 1990s. When the media reported from the battlefield, each side in the conflict called the other in the most derogatory words and expressions, which were dug up from vocabulary used in the past, such as “Ustasha”, “Chetnik”, “Balija” to much more ominous ones, such as “Alija’s rapists and haters”, referring to politician Alija Izetbegovic who was the leader of Bosnian Muslims or Bosniaks as they later identified themselves.

So, what the media industry started then continues today and is exacerbated by the potential provided by new digital technologies, allowing users themselves to comment on texts posted in online editions of traditional media or on new media portals, or to speak their mind on social media. The very possibility of being anonymous and the absence of a clear boundary between the private and the public in the online sphere has contributed to the fact that many have forgotten about civility in communication.

“Street slang and curse words have become commonplace in public communication, in parliament, in political life in general. The reason for this is not the lack of linguistic or political culture, but a deliberate policy of verbal violence” (Ranko Bugarski, NIN, 19.11.2020, page 20). It is about exerting power through linguistic choices, which political ruling elites practice on a daily basis in communication with journalists, the public, and politicians.

The model of public communication they have established is also becoming the model of “best” practice for others, a pattern according to which anything goes, regardless of whether it crosses the boundaries of basic decency and enters the area of open verbal violence. If the statements of Members of Parliament are not sanctioned, like the one of Voislav Šešelj, which is one of the countless examples of hate speech spoken behind the rostrum of the most democratic body of every society, then it is impossible to expect different models of communication to be present in public discourse in other spheres: “You know, you have heard of Snezana Chongradin, she is very ugly, uglier even than Stasa Zajovic. Stasa Zajovic is a catch compared to her. She looks like a mongoose. A real mongoose, I swear on my life. Can you imagine that Snezana Chongradin, who looks like a mongoose, wrote…”.

And what does the online community write?

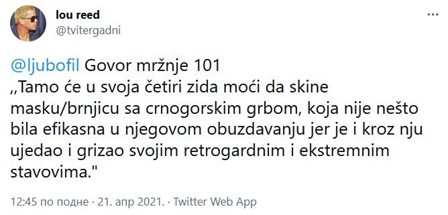

No one gets worked-up anymore about the statements coming from the parliamentary rostrum that insult all those who are not us, because they have become part of the daily “parliamentary repertoire” and the fight “for a better tomorrow”. The online community cares even less about etiquette in public discourse. Such posts on Twitter are part of the daily offer of hate speech and expression of intolerance towards people with different opinions, even when they condemn hate speech:

“There, within his four walls, he’ll be able to take off his mask bearing the Montenegrin Coat of Arms, which really did not help to contain him, for he bit and chewed through it with his retrograde and extremist opinions.”

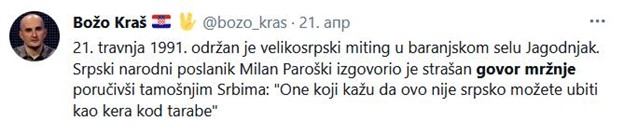

On April 21 1991, an All-Serb rally was organized in the village of Jagodnjak in Baranja county. The Serbian MP Milan Paroshki spewed terrible hate speech, telling the Serbs who live there: “You can kill whoever says that this is not Serbian, as if they were a dog near the fence”.

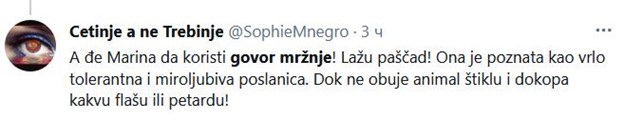

Where would Marina use hate speech? Lying dogs! She is known for being a tolerant and peace-loving MP. Until she puts on animal-print high heels and gets her hands on a bottle or a fire cracker!

Is there a pattern that is followed without a second thought?

Hate speech has clear patterns at the explicit and the implicit level i.e., concerning both content and form. The content is easily recognizable, chiefly through the vocabulary that is obscene and obscure and not appropriate for public speech, but it is also easiest to identify and if there is a desire, it can be easily excluded from public communication by simply moderating user comments on a news portal, filtering out such content. Actually, anyone who does not want their “personal space” to be polluted, they can block people who spread hate speech on Twitter or unfriend them on Facebook. For the most part, lexical aggression is absent in traditional media, with the exception of tabloids.

According to the research of CEPROM “Communicative aggression in Serbia 2019”, aggressive communication is six times more present in the online sphere compared to print media, because as many as 86 percent (17,169 texts) of problematic texts containing hate speech, sensationalism and aggression were published on news portals, while 14 percent (2 795 texts) were published in the daily press.”

The situation is much more complicated with narratives and discourse strategies that implicitly spread hatred and intolerance towards those who do not belong in one’s group or have a different opinion, in both traditional and new media. In order to deconstruct discourse strategies, we still need a scientific apparatus, and therefore researchers have a big and serious task to analyse the public speech of “symbolic elites” (a term of Teun A. van Dijk) in the Western Balkans, which have contributed to communicative pollution of public space. Journalists, writers, publicists, directors, actors, and other representatives of the creative industry are considered to be part of the symbolic elites, because they are the ones who can subtly mediate hate speech on behalf of the political ruling power in a way that is not clearly identifiable and therefore the audience’s defence mechanisms are not prepared and often do not react at all.

There are countless examples, especially in the media. It is enough to convey the words of participants in events that spread hate speech without adding any comment, or to publicise an event that does not deserve it, because it is not significant enough to be considered “of public interest” i.e., that certain subjects of social practice are never quoted directly in the media because they do not belong to ruling elites, and others dominate TV air-time with public appearances because they have the power in society to speak whenever and wherever they wish, whatever the occasion and whatever is on their mind. For example, in 14 analysed editions of the prime-time television news of the Serbian public broadcasting service, Aleksandar Vučić was quoted 28 times, on average twice per edition.

If a certain social group is always portrayed in a negative context, regardless of its actual public appearances, actions, or inactions, that also constitutes hate speech, which is always the case when it comes to opposition leaders in the Western Balkans. Contrary to this, the statements of young leaders of the ruling party are ever-so-present in the media, and they use every opportunity in the Assembly to speak negatively about the opposition, which, by the way, is not even present in the national parliament. Whatever the topic, it is only important to mention the opposition in a negative context, because firstly, the sessions are broadcast live, and secondly, the media and social media cite it abundantly later on, making the popularity grow: Luka Kebara “Just look at how former tycoon politicians like Mr. Dragan Đilas or Mrs. Marinika Čobanov-živka-morović Tepić, they were among the first to say that the vaccine was not good, that our state was not able to procure those vaccines, and they were among the first to run and get a jab of that vaccine at the first chance they got. And they received vaccines from various producers, members of their party, that banana-party, freedom, justice, whatever its name is, an irrelevant party”.

Who are the best target practices for hate speech?

In the Western Balkans, they are always the same subjects, those who do not possess any social power, being a convenient group to be subject of attack so as to divert the public’s attention from much more important topics, such as various wrongdoings of those who have that power. So, in addition to the opposition, there are also migrants, journalists who criticise the government, marginalized groups, national minorities, and the LGBT population.

The media have power and use it extensively in the Western Balkans to produce and spread “moral panic” and further marginalize societal groups by condemning them with the abundant use of hate speech, as symptoms and causes of wider social tensions and immorality of all kinds, be it disinformation, manipulative content or fake news.

The patterns are always the same, and these specific examples are only nuances of the manifestation.

Author: Dubravka Valić Nedeljković, PhD

The artickle was first pubnished in ResPublica, where you can read it in Albanian, Macedonian and Bosnian/Montenegrin/Serbian.

Photo credit: Andrii Yalanskyi/ Shutterstock